More Details

1. Preface

In August 2024, the Taiwan Intellectual Property Office (TIPO) released an analysis of Taiwan’s Green Trademark Industry. The report presents data on the number of applications, percentages and trends in different categories as well as the ratio of Taiwanese applicants and foreign applicants based on the database of the TIPO within the period from 2014 to 2023. The large scale of analysis provides an opportunity to outline the current development of “Green Industry” and predict possible trends in the future. With reference to the conclusions of the analysis, the sectors of industry, government and academia may be better informed when making strategies related to green products and services. This article reviews observations made by the TIPO from analysis of Green Trademark applications and policies that have been or will be implemented to address environmental issues, which enables the readers to better understand the relationship between Green Trademarks and the policies of Green Industries.

2. The definition of “Green Trademarks” and “Green Industry”

The term “Green Trademarks” refers to trademark applications that designate at least one “green good or service” in their identification, instead of describing the pattern or illustration of such trademark.[1] The word “green” indicated in the forgoing description refers to products and services that require the use of fewer resources, have a smaller impact on the environment and are designed to last longer when compared to similar ones.[2]

Green goods and services are often associated with the term “Green Industry,” which describes businesses of different fields that make existing products more environmentally friendly and deliver environmental goods and services.

The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) coined the concept of “Green Industry” as economies striving for a more sustainable pathway of growth, by undertaking green public investments and implementing public policy initiatives that encourage environmentally responsible private investments.[3]

Therefore, “green products or services” do not belong to a certain group of the Nice Classification or belong to any field of industry in a country; instead, they are distributed in multiple groups of the classification and various fields of industry. The foregoing background accentuates the importance of separating goods and services according to their natures when analyzing Green Trademarks, for which a classification system of nine groups and thirty-five categories as indicated below was adopted when the TIPO studied the Green Trademarks in Taiwan.

3. The nine groups of Green Trademarks and the categories of these groups

The classification system of nine groups and thirty-five categories originates from the EUIPO, which used its “Harmonised Database” as a base to sort out the groups and categories of the products and services of Green Trademarks.[4] Each group has different numbered categories, and there are thirty-five categories in total. Each category may refer to a certain good/service or a collection of various goods/services. The nine groups and the thirty-five categories are listed in the following chart:

.png)

The TIPO uses the same classification system as the EUIPO to analyze the database of trademarks in Taiwan so that the results obtained may be used to compare with the analysis from the EUIPO.

4. The overall observation on the applications for “Green Trademarks” filed by Taiwanese and foreign applicants

The total number of Green Trademark applications filed in Taiwan between 2014 and 2023 is 125,388, but under the consideration that one mark may include multiple classes and various goods, which may respectively be classified in different groups of Green Trademarks, the total number of Green Trademark applications should be adjusted to 168,892.

(1) Numbers of applications in the nine groups

.png)

The top three groups of Green Trademarks filed in Taiwan are “energy conservation,” “pollution control” and “energy production,” which respectively and roughly account for 32%, 27% and 21% of Green Trademarks filed in Taiwan. In total, these three groups roughly account for 80% of the Green Trademarks in Taiwan.

(2) Difference between Taiwanese applicants and foreign applicants

Among the 125,388 Green Trademark applications filed in Taiwan between 2014 and 2023, Taiwanese applicants account for 64.46%, while foreign applicants account for 35.54%.

Among the foreign applicants, applicants from China, the U.S.A. and Japan filed the most Green Trademarks in Taiwan. China accounts for more than nine percent of applications in “energy production,” “transportation” and “energy conservation.” The U.S.A. accounts for more than nine percent of applications in “energy production,” “environmental awareness” and “climate change.” Japan accounts for eight percent of applications in “transportation,” “reuse/recycling,” “pollution control” and “waste management.”

In most categories, Taiwan accounts for about sixty percent of applications, but relatively low percentages are observed in “energy production” and “transportation.” The countries that filed the most Green Trademarks in Taiwan and the numbers of applications are indicated as follows:

.png)

(3) Numbers of applications in the thirty-five categories

.png)

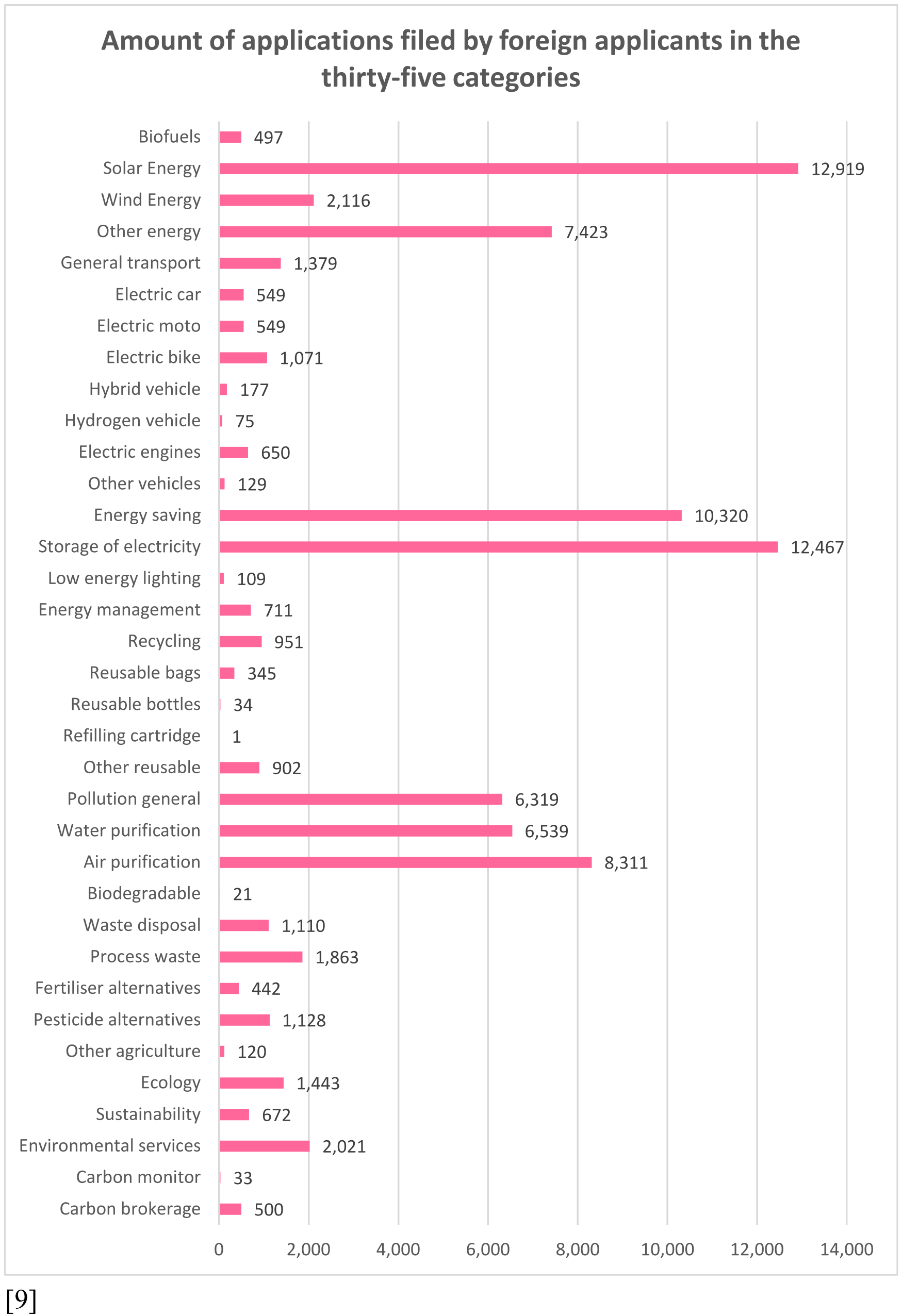

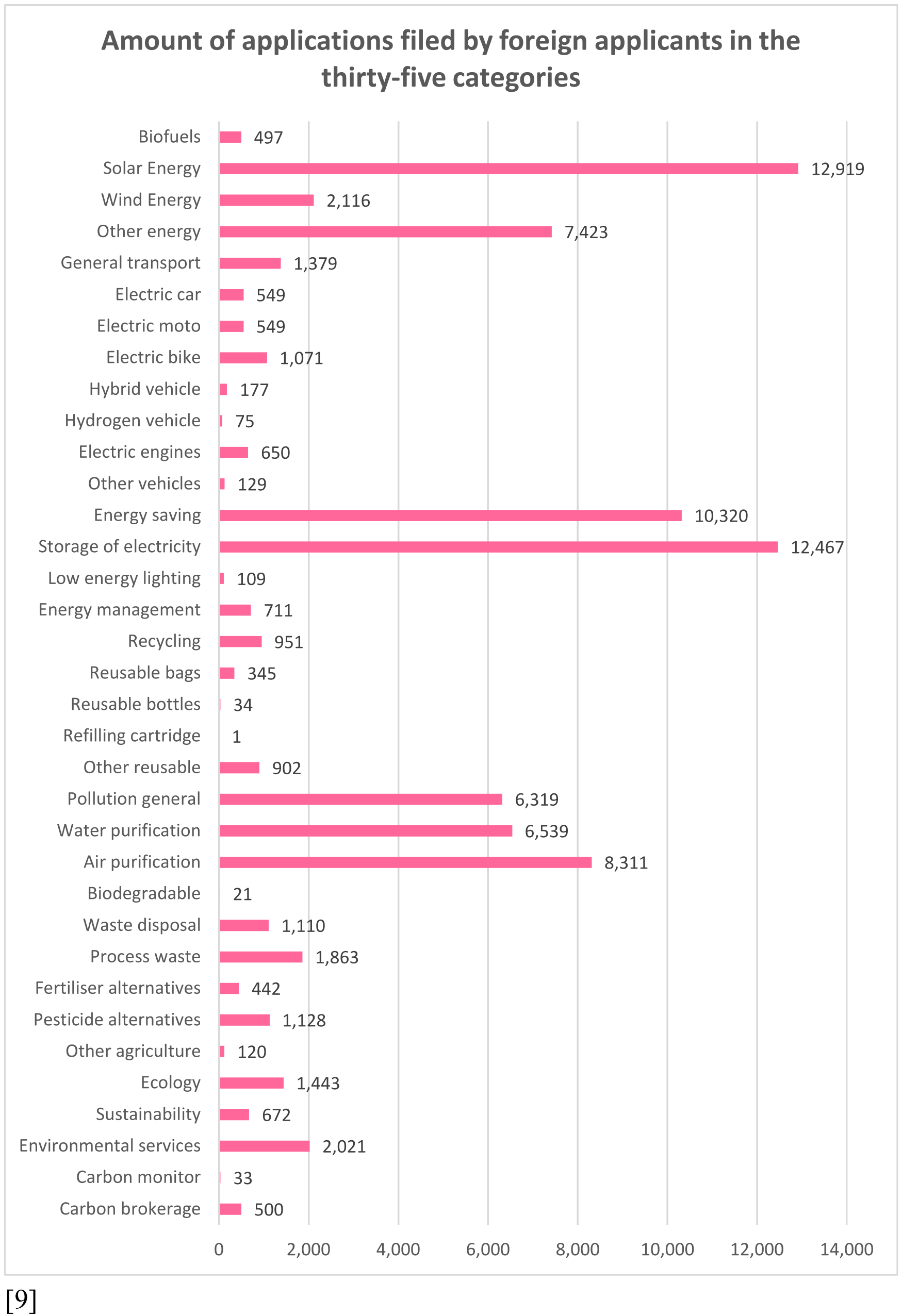

“Solar energy,” “storage of electricity,” “energy saving” and “air purification” are the top four categories of the Green Trademarks filed by foreign applicants in the ten-year period, and respectively have 12,919, 12,467, 10,320 and 8,311 applications. The categories “refilling cartridge,” “biodegradable,” “carbon monitor” and “reusable bottles” are the last, with each having under one hundred applications in the ten-year period. The numbers of the applications filed by foreign applicants in each category is indicated as follows:

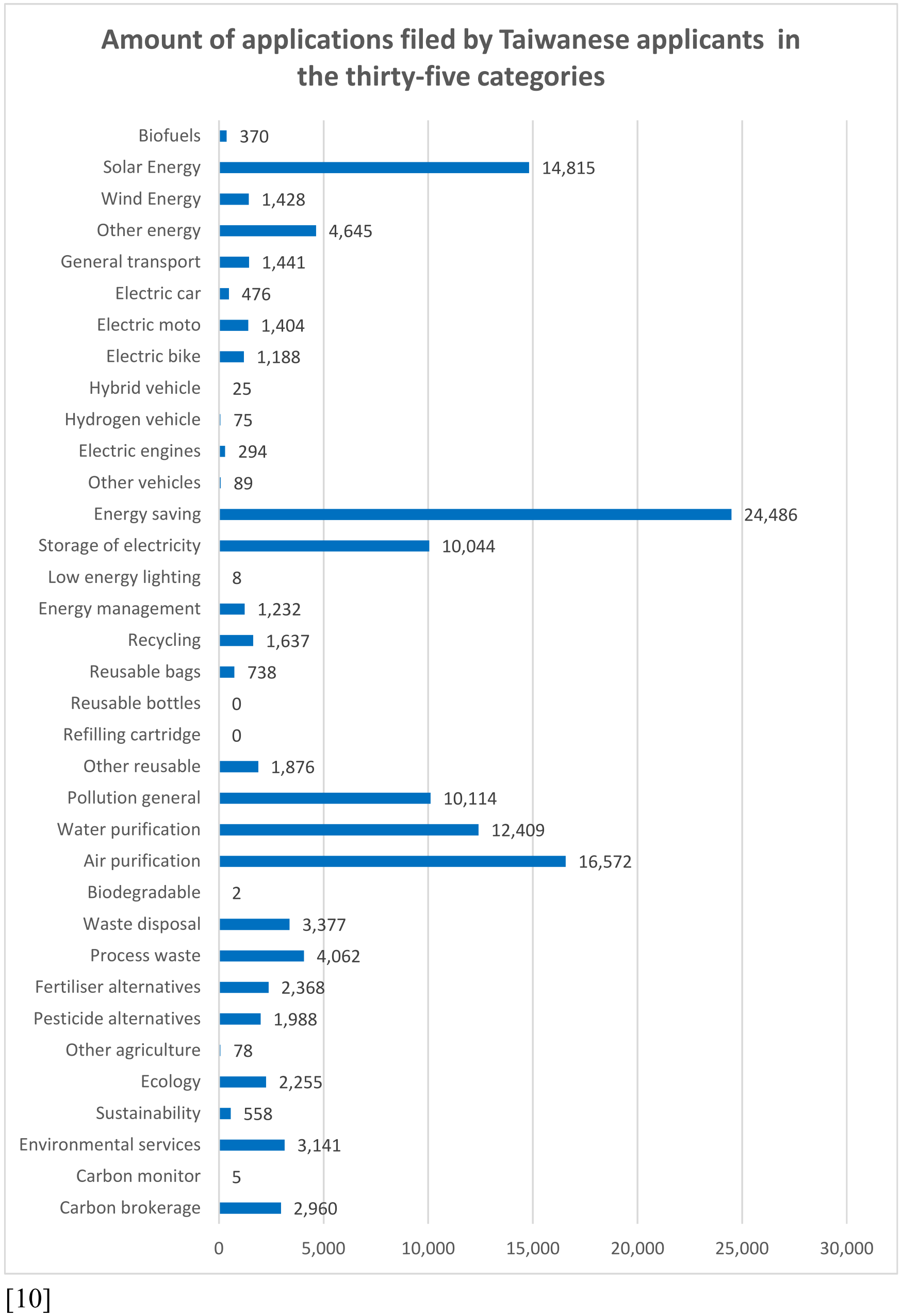

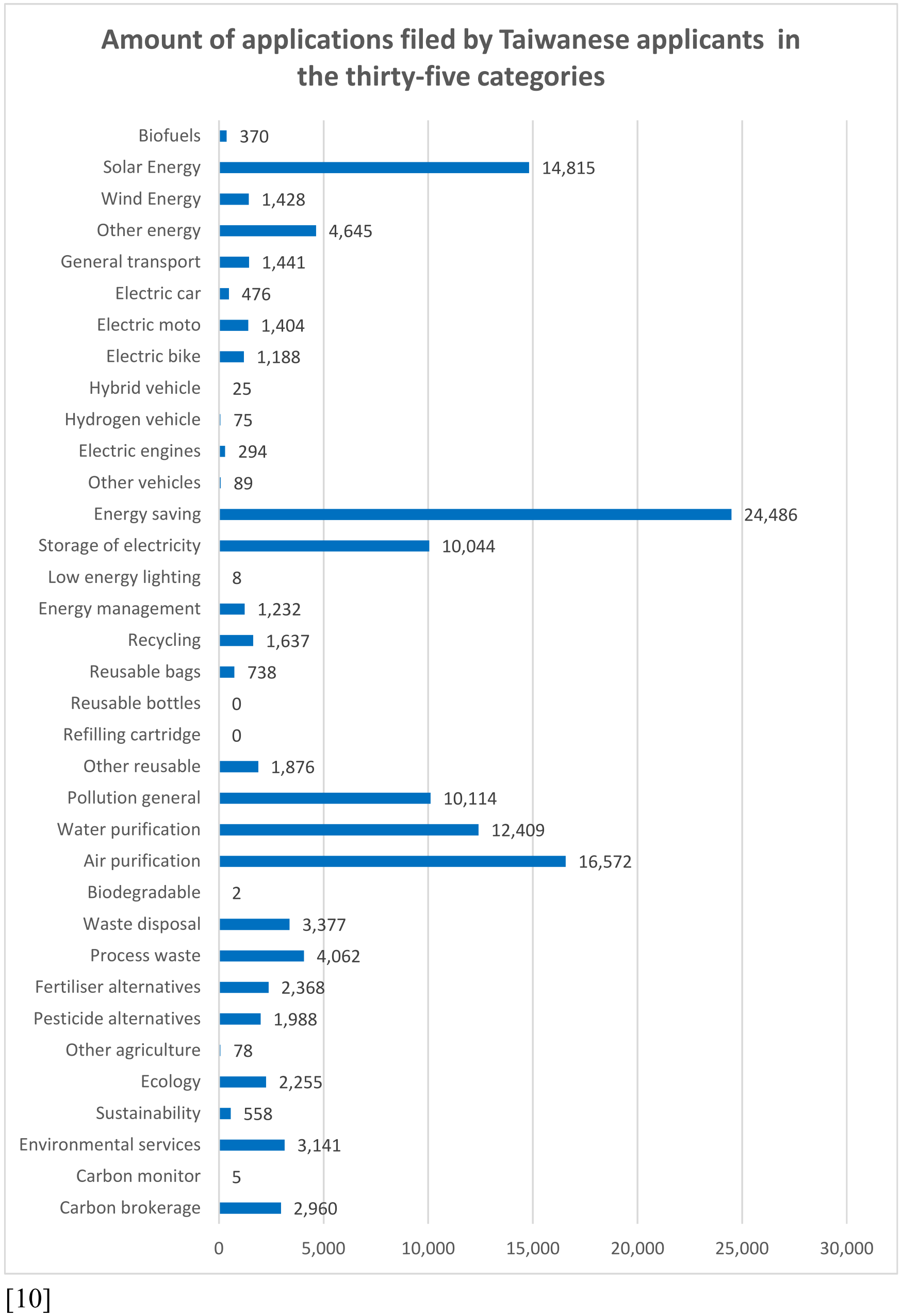

“Energy saving,” “air purification,” “solar energy” and “water purification” are the top four categories of the Green Trademarks filed by Taiwanese applicants in the ten-year period, and respectively have 24,486, 16,572, 14,815 and 12,409 applications. The categories “refilling cartridge,” “reusable bottles,” “biodegradable” and “carbon monitor” are the last, with each having under ten applications in the ten-year period. The numbers of the applications filed by Taiwanese applicants in each category is indicated as follows:

5. The major environmental policies in Taiwan

The government’s environmental policy focuses on “moving towards a circular economy,” “cleaning the air,” “improving water quality” and “caring for our land.”[11] Details of the policies with respect to the foregoing four issues are indicated as follows:

(1) Moving towards a circular economy

In the past, the principle of treating waste disposal was incineration as the main approach and landfills as the auxiliary method. Since 2003, the government started to promote “reducing waste generation at the source.” [12] The Ministry of Economic Affairs of the Executive Yuan issued the “Circular Economy Promotion Plan” at the end of 2018, aiming to transition industrial development from a linear economy to a circular economy.

The specific measures executed under the “Circular Economy Promotion Plan” are assisting the key industries to develop innovative material technologies and recycled resources of high value, building new recycling demonstration sites, promoting green consumption patterns and government green procurement and strengthening recycling systems. [13]

(2) Cleaning the air [14]

In order to comprehensively improve the air pollution problem, the government announced the “Air Pollution Prevention Strategy” in 2017 and started to implement the “Air Pollution Prevention Action Plan” to target the three controllable pollution sources respectively from industries, traffic and others. In 2018, the “Air Pollution Control Act” was amended with the direction of building a more complete air quality management system. In 2020, a new version of the “Air Pollution Control Program” was initiated to improve pollution from both the source and the end.

The specific measures executed under the “Air Pollution Control Program” are establishing a management system of permit and fuel use for fixed pollution sources, implementing an air pollution reduction plan and boiler improvement for state-owned enterprises, strengthening continuous automatic monitoring of fixed pollution sources, revising relevant regulations on air pollution control fees, accelerating the replacement of motorcycles and large diesel vehicles, adding standards of maximum content of sulfur for ship fuel, replacing all urban buses with electrical buses, controlling building and industrial maintenance paints sold on the market, requiring the catering industry to manage cooking oil fume, and restraining open-air burning behavior.

(3) Improving water quality [15]

Regarding the protection of the water quality, the government focuses on four aspects, namely promoting the green transformation of wastewater treatment, improving the management of river water, promoting the “Total Mass Control of Water Pollution” 2.0 plan and strengthening the detection and control of drinking water quality.

The green transformation of wastewater treatment mainly involves including anaerobic treatment methods in the treatment of high-organic wastewater to produce reusable biogas, guiding recycling and reuse of nitrogen/phosphorus/metal and other material resources in wastewater and adopting low-carbon and energy-saving technologies with smart water management by developing relevant technology and giving subsidies to qualified business.

As to the management of river water, the emphasis is put on the inspection and control of industrial pollution by connecting relevant environmental authorities with the police. Through the implementation of the “Total Mass Control of Water Pollution” 2.0 plan, more river monitoring stations for detecting heavy metals that exceed standards and pollution of a medium-to-severe degree were set up and stricter standards of water flow or mass control of water pollution are enforced according to the local conditions.

As to drinking water quality, it is mainly regulated by the “Drinking Water Management Act,” which regulates drinking water sources, the regulation of water treatment chemicals and drinking water quality standards.[16] The government has planned to strengthen the management of drinking water quality, and thus the standard of controlling “Poly fluoro alkyl substances (PFAS)” will be included in the “Drinking Water Quality Standard,” which will be a leading mandatory standard in Asia and will be implemented in July 2027.

(4) Caring for our land

In view of the impact arising from climate change around the world, the Taiwan government published a plan in March 2022 demonstrating Taiwan’s Pathway to Net-Zero Emissions in 2050, followed in December by an action plan for 12 key strategies for net-zero transition, and in January 2023 approved a 2023-2026 plan outlining various carbon reduction methods and adjustments to bring the nation closer to Net-Zero. For the purpose of caring for our land by pursuing the goal of Net-Zero, various strategies are carried out in Taiwan, and these strategies are briefly indicated as follows:

(a) Decarbonizing electrical energy [17]

The main strategy of renewable energy will be developing wind power and photovoltaic power. The government is moving the development of wind power towards large-scale and floating offshore wind turbines. It is planned that the installed capacity of offshore wind power will create 13.1GW before 2030 and 40~55GW before 2050. The government will also expand the installation of photovoltaic power through diversified land application; they will also replace and update the installations with new generation high-efficiency photovoltaic power equipment. It is planned that the installed capacity of solar photovoltaic installations will reach 30GW before 2030 and 40~80GW before 2050.

As to other forms of renewable energy, such as hydrogen energy, geothermal energy, ocean energy and biomass energy, the government is proceeding with the development of relevant basic technologies in these fields. Relevant infrastructure for use on hydrogen reception, transmission and storage, as well as hydrogen utilization systems will gradually be deployed by the government. The government has planned to gradually develop non-traditional geothermal power generation from shallow layers to deep layers and ocean energy technologies such as power generation by wave and ocean current. The use of biomass energy will also be expanded by combining resources both from domestic recycling and imports to stabilize the source of biomass materials.

(b) Promoting resource recycling and changes in behaviors [18]

The government is improving the reduction of products from their sources by promoting green design and green consumerism. They are also trying to use waste materials as resources and strengthen sustainable resource recycling by linking the upstream, midstream and downstream industries to form a resource recycling industry chain. They plan to invest in technology research, development and innovation that would be beneficial to improve resource recycling efficiency, and this is based on the four major aspects of product design, resource recycling, industrial linkage and technological innovation.

The government is promoting “Net-Zero Green-Life” with a focus on food, clothing, housing, transportation and others. The government will maintain a consensus through dialogue in the public and promote the education of changing behavior, with an aim to build a low-carbon business model and create a green-life industry chain.

(c) Developing carbon capture and storage

The government will use the technology of “Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS)” to remove carbon emissions from industries and energy facilities, and priority is given to the development of the technology of carbon capture and utilization, which will recycle and utilize CO2 from the petrochemical industry and use it in the manufacture of raw chemical materials and building materials and thus establish a carbon cycle chain.

As afforestation and related management can reduce carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere, the government has plans to develop carbon-negative farming methods, protect marine habitats, develop animal and plant conservation technologies, protect biodiversity, prevent soil erosion and conserve forests.

(d) Improving the efficiency of energy [19]

In all aspects, including manufacturing, home living, commercial services and transportation, the government will quickly expand the application of mature technologies to improve energy efficiency. Through economic incentives, educational guidance and mandatory regulations, the aim is to raise the market penetration rate of high-efficiency equipment.

The specific measures are encouraging the manufacturing industry to replace old industrial equipment and use alternative energy sources, such as natural gas, biomass energy and solar energy, guiding users in commercial department with high demand of power to implement the requirements of annually saving 1% electricity energy on average and regulating the energy efficiency of equipment, as well as replacing old equipment such as air conditioning equipment and lighting equipment through means of on-site counseling, promotion activities, tax exemptions or subsidies, etc. For a further step, the government has scheduled to amended the Energy Administration Act to increase the numbers of penalties and to publish lists of violators, etc. In the meantime, the government will develop innovative new energy efficiency technologies and gradually introduce forward-looking technologies to comprehensively improve energy efficiency from the demand side.

Regarding the aspect of transportation, the main strategy is to replace traditional fuel vehicles with electric vehicles. To achieve such goal, the government plans to have urban buses fully rely on electric power by 2030, to have the annual market share of electric cars reach 30% of all new cars by 2030 and to have the annual market share of electric motorcycles reach 35% of all the new motorcycles by 2030. In order to proceed with such transformation, the government is developing upstream and downstream industries related to electric vehicles, and integrating the technical research and development and the establishment of infrastructure such as energy storage, charging piles and safe charging in buildings. As for large tour buses and large trucks for long-distance travel, there will be plans for the electrification for vehicles according to the development of related industry technology.

(e) Strengthening energy storage [20]

The government is proceeding with decentralizing power grids and enhancing their resilience. With the help of IoT technology which enhances system integration and expands energy storage system settings, the aim is to promote the digitization of power grids and improve operational flexibility and adaptability. They will also develop key energy storage technologies, and launch incentives for business models on energy storage.

6. Brief interpretation on the relationship of the Green Trademarks and the policies of Green Industries

(1) The increase of “Green Trademarks” in certain fields may be related to the direction lead by the policies of “Green Industry.”

For several years, the government has been appealing to the public the importance of “Energy Conservation and Carbon Reduction” and has been preparing relevant plans and regulations for building an all-directional “Green Industry.” Following the publishing of the plan for Taiwan’s Pathway to Net-Zero Emissions in 2050, we can see that the government intends to place emphasis on utilizing photovoltaic power, maximizing saved energy and removing carbon emissions.

As “solar Energy” can be applied to various uses in manufacturing, building, transporting or general living and the locations where the installations can be built have less restriction, it is easy to understand that “solar energy” will be the main force of renewable energy. While using renewable energy, it is important to stabilize the provision of energy so that the public will not suffer from black-outs, requires a good system for storing energy. As renewable energy cannot be completely applied to all the use of electricity in Taiwan, there are various non-renewable resource still in use, which would rely on relevant measures to purify the air. Viewing from this perspective, the government’s emphasis placed on strengthening energy storage and removing carbon emissions seems reasonable.

The analysis of Green Trademarks indicates that “solar energy,” “energy saving,” “air purification” and “storage of electricity” are the top categories for applications, each respectively having 27,728, 34,779, 24,867 and 22,504 applications in the ten-year period. This phenomenon seems to reflect that policies implemented in Taiwan under the Net-Zero plan which focus on certain fields have led to an obvious increase in the numbers of Green Trademarks in such fields.

Despite that the energy conversion efficiency of hydrogen energy is above 50%[21], which is obviously much higher than the 20% [22] for the conversion efficiency of photovoltaic power, the number of applications for “other energy” in the ten-year period is 12,065, which is far less than the 27,728 for “solar Energy.”

Considering that hydrogen energy technology in Taiwan is currently in the stage of research and development and demonstration, the products that utilize hydrogen energy may be very few in contrast to the ones that use solar energy, which may explain the gap in the numbers of the trademark applications between for “solar energy” and “hydrogen energy.”

The same situation may also explain the low numbers of applications in the categories of “electric car” and “storage of electricity.” However, as some breakthroughs have recently been made in these fields, such as the development of “magnesium-based hydrogen storage materials”[23] and “all-inorganic electrolyte batteries,”[24] a growth of the numbers of applications in these fields is expected.

(3) The numbers of “Green Trademarks” filed by foreign applicants may be subject to consideration of cost.

For most of the categories of Green Trademarks, the number of applications filed by Taiwanese applicants are much more than the ones filed by foreign applicants, but some of the categories of green trademarks are not the same. For example, the numbers of applications in “low energy lighting” filed by foreign applicants in the ten-year period is 109, while the amount filed by Taiwanese applicants is 8.

This is a strange situation, as many places have been using low energy lights, such as street lights, markets, factories and offices. Despite that there are various types of low energy lights available, the common ones are LED and compact fluorescent lamps (CFL).

According to relevant reports, manufacturers in Taiwan were dedicated to the development of LED lighting in early years, for which most of them set their main production base in Taiwan. However, they are now unable to compete with China, which has adopted a low-price strategy, resulting in only a few local manufacturers keeping their business in Taiwan. Since most of the progress of the production of LED lights has moved to China, the domestic need for LED lights is mainly supported by imports.[25]

With this background, we may infer that because the manufacture of LED lights is mainly based in China, other countries were not able to keep pace due to the consideration of cost and thus withdrew themselves from the LED market in Taiwan. The same situation may also explain the low numbers of applications filed by Taiwanese applicants in the categories of “electric engines” and “wind energy.”

Under such circumstance, unless more cost-effective products are further developed, it seems hard to attract applicants in different countries to apply for trademarks in Taiwan, which may serve as a reference for the government on making policy in the future.

(4) The policies are moving toward making the regulations tighter to ensure that the environmental regulations will be complied with.

As we can see in the foregoing introduction of the policies, tax exemptions or subsidies are used as common policy instruments for promoting the relevant programs related to environmental issues. However, the outcomes of such approach may not be ideal.

Taking the goal of promoting energy-saving for example, the vast majority of Taiwan’s commercial service industry is small and medium-sized enterprises, which have relatively limited resources to use. In the cases that the investment in energy-saving equipment is high and electricity accounts for a low part in the costs (accounting for only 1% to 8% of the costs for operation), the business may have limited willingness or ability to replace their old equipment.[26] The government may already be aware of such situation and plan to amend the “Energy Administration Act” by increasing the numbers of penalties and disclosing the violators so that obligations of complying with energy-saving regulations may be imposed to businesses.

Viewing from the foregoing trend, compulsory measures are gradually replacing encouraging measures in the environmental issues, which may imply that the numbers of Green Trademarks of some categories currently with few applications, such as “reusable bottles,” “refilling cartridge,” “biodegradable” and “carbon monitor” may have a chance to increase when the compulsory measures are in effect.

(5) There may be bias with regard to the truthfulness of the numbers of “Green Trademarks” due to the statistical methods applied.

The TIPO defines “Green Trademarks” by the designated goods and services contained in the trademark applications and their Nice classification. According to the TIPO’s report, as long as an application designates at least one green product or service, it will be regarded as a “green trademark,” regardless of whether such mark contains other non-green products or services. Therefore, assuming a case in which a trademark is filed with one application designating twenty green products and a case in which a trademark is filed with ten applications each designating one green product, the former is regarded as only one green trademark while the latter is regarded as ten green trademarks, even if the green products of the former are twice the amount of the latter. Under such circumstances, it seems that each green trademark does not have the equal value.

Since the TIPO collected the data of applications, instead of registrations, the active “Green Trademarks” may be much less than the amount indicated in the report. As there may be questions regarding the description of goods/services or the registrability such as being non-distinctive or being similar to other prior marks, a trademark application may finally be dismissed or rejected by the TIPO. As a consequence, a certain growth rate in the applications for “Green Trademarks” does not mean that such growth rate can also be expected for active “Green Trademarks.”

The TIPO’s report collects applications which designate goods and services that fall in the nine groups and the thirty-five categories of “Green Trademarks.” However, as many applicants would like the scope of protection of their marks to be as broad as possible, they would chose a broader term for the designated goods/services even if they actually produce products that are good for the environment. In that scenario, those marks will not fall in the nine groups and the thirty-five categories and thus will not be considered as “Green Trademarks.” For example, a company produces plastic bags made of biodegradable material. Under the concern that other companies which make plastic bags may use a mark similar to their mark, said company may decide to apply for a trademark designating the goods “bags of plastics, for packaging,” and their mark accordingly will not be deemed as a “Green Trademark.” Assuming that there are a large number of applications having an experience the same or similar to the foregoing example, the actual “Green Trademarks” indicated in the report may actually be underestimated.

Despite the bias with regard to the truthfulness of the numbers of “Green Trademarks” as indicated above, the TIPO’s report still points out the overall trend in each category of “Green Trademarks,” which may provide insights for businesses on how to strategically position their green trademark as well as for the government on how to plan the policies addressing environmental issues.

7. Conclusion

Although the development of technology and the consideration of cost as well as other factors may have an impact on the numbers of “Green Trademarks,” as mentioned above, there is no denying that the policies implemented still serve as the main driving force for the increase of “Green Trademarks.”

Considering that the Net-Zero Emissions have set up goals for various departments related to the “Green Industry,” such as to install offshore wind power of the capacity of 13.1GW before 2030, to install solar photovoltaic installations of the capacity of 30GW before 2030, to have the annual market share of electric cars reach 30% of all the new cars by 2030 and to have the same of electric motorcycles reach 35% by 2030, as well as that the government has plans to tighten up regulations related to environmental issues, it is highly possible that the numbers of “Green Trademarks” for most categories will continue to grow in the following years.

With the expectation of the growth of “Green Trademarks” in the future, it is inevitable that some of “Green Trademarks” will come into conflict with each other, for which a layout for trademarks is advised to be conducted in advance as the same would help the businesses in “Green Industry” in protecting their brand value and reducing the risk of infringement. We at Tai E will of course be pleased to provide any possible assistance with all kinds of trademarks, including “Green Trademarks.”

【References】

[1] Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p. 1-2 (2024)

[2] The website of IGI Global Scientific Publishing, https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/implementation-of-green-considerations-in-public-procurement/70836 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[3] The website of United Nations Industrial Development Organization, https://www.unido.org/our-focus-cross-cutting-services-green-industry/green-industry-initiative (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[4] Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.12 (2024)

[5] Source: European Union Intellectual Property Office, Green EU trade marks Analysis of goods and services specifications, 1996-2020, p.24 (2021)

[6] Source: Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.14 (2024)

[7] Source: Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.16 (2024))

[8] Source: Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.35 (2024)

[9] Source: Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.33 (2024)

[10] Source: Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.31 (2024)

[11] The website of Executive Yuan, https://www.ey.gov.tw/state/4AC21DC94B8E19A8/bea31948-b13c-4bd7-b13b-904a50ee5730 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[12] Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research, Report of Taiwan’s Green Industry – An overview of Taiwan's Environmental Protection Industry Development (臺灣綠色產業報告-台灣環保產業發展概況), p.6 (2018)

[13] The website of Executive Yuan, https://www.ey.gov.tw/Page/5A8A0CB5B41DA11E/18ef26a4-5d05-4fb3-963e-6b228e713576 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[14] The website of Executive Yuan, https://www.ey.gov.tw/Page/5A8A0CB5B41DA11E/e8819567-8f04-42e1-84ef-cbbe48b5cce2 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[15] Department of Water Quality protection, The 11th Legislative Yuan 3rd session written report material (立法院 11-3 會期書面報告資料), p.1-4 (2024),

https://water.moenv.gov.tw/Public/Download/Policy_law/%E7%AB%8B%E6%B3%95%E9%99%A211-3%E6%9C%9F%E6%9B%B8%E9%9D%A2%E5%A0%B1%E5%91%8A-%E6%B0%B4%E8%B3%AA%E4%BF%9D%E8%AD%B7%E5%8F%B8.pdf

[16] Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research, Report of Taiwan’s Green Industry – An overview of Taiwan's Environmental Protection Industry Development (臺灣綠色產業報告-台灣環保產業發展概況), p.11-12 (2018)

[17] National Development Council, Taiwan's 2050 Net Zero Emissions Pathway and Strategy Overview (臺灣2050淨零排放路徑及策略總說明), p.72-73 (2022)

[18] National Development Council, Taiwan's 2050 Net Zero Emissions Pathway and Strategy Overview (臺灣2050淨零排放路徑及策略總說明), p.74-75 (2022)

[19] National Development Council, Taiwan's 2050 Net Zero Emissions Pathway and Strategy Overview (臺灣2050淨零排放路徑及策略總說明), P.19-31 (2022)

[20] National Development Council, Taiwan's 2050 Net Zero Emissions Pathway and Strategy Overview (臺灣2050淨零排放路徑及策略總說明), P.71 (2022)

[21] The website of Industrial Technology Research Institute, https://www.itri.org.tw/ListStyle.aspx?DisplayStyle=18_content&SiteID=1&MmmID=1036452026061075714&MGID=1307347607677744430 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[22] The website of Green Energy & Environment Research Laboratories, https://www.re.org.tw/news/more.aspx?cid=200&id=2448 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[23] National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, https://www.ntust.edu.tw/p/406-1000-128936,r167.php?Lang=zh-tw (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[24] Chen-Yu Zhang (張宸毓), 2025 CES: ProLogium Technology 's 4th generation lithium ceramic battery achieves 4-minute fast charging along with minus 20 degrees Celsius test, and is expected to be mass-produced by the end of 2025,January 8, 2025,The website of U-CAR, https://news.u-car.com.tw/news/article/82418 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[25] The International Trade Administration, Report of Taiwan’s Green Industry – From the perspective of the changes in the Global Lighting Industry to see the Market Trends and Challenges (台灣綠色產業報告-由全球照明產業轉變,看市場發展趨勢與挑戰), p.9 (2018)

[26] National Development Council, Taiwan's 2050 Net Zero Emissions Pathway and Strategy Overview (臺灣2050淨零排放路徑及策略總說明), p.80 (2022)

In August 2024, the Taiwan Intellectual Property Office (TIPO) released an analysis of Taiwan’s Green Trademark Industry. The report presents data on the number of applications, percentages and trends in different categories as well as the ratio of Taiwanese applicants and foreign applicants based on the database of the TIPO within the period from 2014 to 2023. The large scale of analysis provides an opportunity to outline the current development of “Green Industry” and predict possible trends in the future. With reference to the conclusions of the analysis, the sectors of industry, government and academia may be better informed when making strategies related to green products and services. This article reviews observations made by the TIPO from analysis of Green Trademark applications and policies that have been or will be implemented to address environmental issues, which enables the readers to better understand the relationship between Green Trademarks and the policies of Green Industries.

2. The definition of “Green Trademarks” and “Green Industry”

The term “Green Trademarks” refers to trademark applications that designate at least one “green good or service” in their identification, instead of describing the pattern or illustration of such trademark.[1] The word “green” indicated in the forgoing description refers to products and services that require the use of fewer resources, have a smaller impact on the environment and are designed to last longer when compared to similar ones.[2]

Green goods and services are often associated with the term “Green Industry,” which describes businesses of different fields that make existing products more environmentally friendly and deliver environmental goods and services.

The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) coined the concept of “Green Industry” as economies striving for a more sustainable pathway of growth, by undertaking green public investments and implementing public policy initiatives that encourage environmentally responsible private investments.[3]

Therefore, “green products or services” do not belong to a certain group of the Nice Classification or belong to any field of industry in a country; instead, they are distributed in multiple groups of the classification and various fields of industry. The foregoing background accentuates the importance of separating goods and services according to their natures when analyzing Green Trademarks, for which a classification system of nine groups and thirty-five categories as indicated below was adopted when the TIPO studied the Green Trademarks in Taiwan.

3. The nine groups of Green Trademarks and the categories of these groups

The classification system of nine groups and thirty-five categories originates from the EUIPO, which used its “Harmonised Database” as a base to sort out the groups and categories of the products and services of Green Trademarks.[4] Each group has different numbered categories, and there are thirty-five categories in total. Each category may refer to a certain good/service or a collection of various goods/services. The nine groups and the thirty-five categories are listed in the following chart:

.png)

The TIPO uses the same classification system as the EUIPO to analyze the database of trademarks in Taiwan so that the results obtained may be used to compare with the analysis from the EUIPO.

4. The overall observation on the applications for “Green Trademarks” filed by Taiwanese and foreign applicants

The total number of Green Trademark applications filed in Taiwan between 2014 and 2023 is 125,388, but under the consideration that one mark may include multiple classes and various goods, which may respectively be classified in different groups of Green Trademarks, the total number of Green Trademark applications should be adjusted to 168,892.

(1) Numbers of applications in the nine groups

.png)

The top three groups of Green Trademarks filed in Taiwan are “energy conservation,” “pollution control” and “energy production,” which respectively and roughly account for 32%, 27% and 21% of Green Trademarks filed in Taiwan. In total, these three groups roughly account for 80% of the Green Trademarks in Taiwan.

(2) Difference between Taiwanese applicants and foreign applicants

Among the 125,388 Green Trademark applications filed in Taiwan between 2014 and 2023, Taiwanese applicants account for 64.46%, while foreign applicants account for 35.54%.

Among the foreign applicants, applicants from China, the U.S.A. and Japan filed the most Green Trademarks in Taiwan. China accounts for more than nine percent of applications in “energy production,” “transportation” and “energy conservation.” The U.S.A. accounts for more than nine percent of applications in “energy production,” “environmental awareness” and “climate change.” Japan accounts for eight percent of applications in “transportation,” “reuse/recycling,” “pollution control” and “waste management.”

In most categories, Taiwan accounts for about sixty percent of applications, but relatively low percentages are observed in “energy production” and “transportation.” The countries that filed the most Green Trademarks in Taiwan and the numbers of applications are indicated as follows:

.png)

(3) Numbers of applications in the thirty-five categories

“Solar energy” “energy saving,” “air purification” and “storage of electricity” are the top four categories of Green Trademarks filed in Taiwan in the ten-year period, and respectively have 27,728, 34,779, 24,867 and 22,504 applications. The categories “refilling cartridge,” “biodegradable,” “reusable bottles” and “carbon monitor” are the last, with each having under one hundred applications in the ten-year period. The numbers of the applications of each category is indicated as follows:

.png)

“Solar energy,” “storage of electricity,” “energy saving” and “air purification” are the top four categories of the Green Trademarks filed by foreign applicants in the ten-year period, and respectively have 12,919, 12,467, 10,320 and 8,311 applications. The categories “refilling cartridge,” “biodegradable,” “carbon monitor” and “reusable bottles” are the last, with each having under one hundred applications in the ten-year period. The numbers of the applications filed by foreign applicants in each category is indicated as follows:

“Energy saving,” “air purification,” “solar energy” and “water purification” are the top four categories of the Green Trademarks filed by Taiwanese applicants in the ten-year period, and respectively have 24,486, 16,572, 14,815 and 12,409 applications. The categories “refilling cartridge,” “reusable bottles,” “biodegradable” and “carbon monitor” are the last, with each having under ten applications in the ten-year period. The numbers of the applications filed by Taiwanese applicants in each category is indicated as follows:

5. The major environmental policies in Taiwan

The government’s environmental policy focuses on “moving towards a circular economy,” “cleaning the air,” “improving water quality” and “caring for our land.”[11] Details of the policies with respect to the foregoing four issues are indicated as follows:

(1) Moving towards a circular economy

In the past, the principle of treating waste disposal was incineration as the main approach and landfills as the auxiliary method. Since 2003, the government started to promote “reducing waste generation at the source.” [12] The Ministry of Economic Affairs of the Executive Yuan issued the “Circular Economy Promotion Plan” at the end of 2018, aiming to transition industrial development from a linear economy to a circular economy.

The specific measures executed under the “Circular Economy Promotion Plan” are assisting the key industries to develop innovative material technologies and recycled resources of high value, building new recycling demonstration sites, promoting green consumption patterns and government green procurement and strengthening recycling systems. [13]

(2) Cleaning the air [14]

In order to comprehensively improve the air pollution problem, the government announced the “Air Pollution Prevention Strategy” in 2017 and started to implement the “Air Pollution Prevention Action Plan” to target the three controllable pollution sources respectively from industries, traffic and others. In 2018, the “Air Pollution Control Act” was amended with the direction of building a more complete air quality management system. In 2020, a new version of the “Air Pollution Control Program” was initiated to improve pollution from both the source and the end.

The specific measures executed under the “Air Pollution Control Program” are establishing a management system of permit and fuel use for fixed pollution sources, implementing an air pollution reduction plan and boiler improvement for state-owned enterprises, strengthening continuous automatic monitoring of fixed pollution sources, revising relevant regulations on air pollution control fees, accelerating the replacement of motorcycles and large diesel vehicles, adding standards of maximum content of sulfur for ship fuel, replacing all urban buses with electrical buses, controlling building and industrial maintenance paints sold on the market, requiring the catering industry to manage cooking oil fume, and restraining open-air burning behavior.

(3) Improving water quality [15]

Regarding the protection of the water quality, the government focuses on four aspects, namely promoting the green transformation of wastewater treatment, improving the management of river water, promoting the “Total Mass Control of Water Pollution” 2.0 plan and strengthening the detection and control of drinking water quality.

The green transformation of wastewater treatment mainly involves including anaerobic treatment methods in the treatment of high-organic wastewater to produce reusable biogas, guiding recycling and reuse of nitrogen/phosphorus/metal and other material resources in wastewater and adopting low-carbon and energy-saving technologies with smart water management by developing relevant technology and giving subsidies to qualified business.

As to the management of river water, the emphasis is put on the inspection and control of industrial pollution by connecting relevant environmental authorities with the police. Through the implementation of the “Total Mass Control of Water Pollution” 2.0 plan, more river monitoring stations for detecting heavy metals that exceed standards and pollution of a medium-to-severe degree were set up and stricter standards of water flow or mass control of water pollution are enforced according to the local conditions.

As to drinking water quality, it is mainly regulated by the “Drinking Water Management Act,” which regulates drinking water sources, the regulation of water treatment chemicals and drinking water quality standards.[16] The government has planned to strengthen the management of drinking water quality, and thus the standard of controlling “Poly fluoro alkyl substances (PFAS)” will be included in the “Drinking Water Quality Standard,” which will be a leading mandatory standard in Asia and will be implemented in July 2027.

(4) Caring for our land

In view of the impact arising from climate change around the world, the Taiwan government published a plan in March 2022 demonstrating Taiwan’s Pathway to Net-Zero Emissions in 2050, followed in December by an action plan for 12 key strategies for net-zero transition, and in January 2023 approved a 2023-2026 plan outlining various carbon reduction methods and adjustments to bring the nation closer to Net-Zero. For the purpose of caring for our land by pursuing the goal of Net-Zero, various strategies are carried out in Taiwan, and these strategies are briefly indicated as follows:

(a) Decarbonizing electrical energy [17]

The main strategy of renewable energy will be developing wind power and photovoltaic power. The government is moving the development of wind power towards large-scale and floating offshore wind turbines. It is planned that the installed capacity of offshore wind power will create 13.1GW before 2030 and 40~55GW before 2050. The government will also expand the installation of photovoltaic power through diversified land application; they will also replace and update the installations with new generation high-efficiency photovoltaic power equipment. It is planned that the installed capacity of solar photovoltaic installations will reach 30GW before 2030 and 40~80GW before 2050.

As to other forms of renewable energy, such as hydrogen energy, geothermal energy, ocean energy and biomass energy, the government is proceeding with the development of relevant basic technologies in these fields. Relevant infrastructure for use on hydrogen reception, transmission and storage, as well as hydrogen utilization systems will gradually be deployed by the government. The government has planned to gradually develop non-traditional geothermal power generation from shallow layers to deep layers and ocean energy technologies such as power generation by wave and ocean current. The use of biomass energy will also be expanded by combining resources both from domestic recycling and imports to stabilize the source of biomass materials.

(b) Promoting resource recycling and changes in behaviors [18]

The government is improving the reduction of products from their sources by promoting green design and green consumerism. They are also trying to use waste materials as resources and strengthen sustainable resource recycling by linking the upstream, midstream and downstream industries to form a resource recycling industry chain. They plan to invest in technology research, development and innovation that would be beneficial to improve resource recycling efficiency, and this is based on the four major aspects of product design, resource recycling, industrial linkage and technological innovation.

The government is promoting “Net-Zero Green-Life” with a focus on food, clothing, housing, transportation and others. The government will maintain a consensus through dialogue in the public and promote the education of changing behavior, with an aim to build a low-carbon business model and create a green-life industry chain.

(c) Developing carbon capture and storage

The government will use the technology of “Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS)” to remove carbon emissions from industries and energy facilities, and priority is given to the development of the technology of carbon capture and utilization, which will recycle and utilize CO2 from the petrochemical industry and use it in the manufacture of raw chemical materials and building materials and thus establish a carbon cycle chain.

As afforestation and related management can reduce carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere, the government has plans to develop carbon-negative farming methods, protect marine habitats, develop animal and plant conservation technologies, protect biodiversity, prevent soil erosion and conserve forests.

(d) Improving the efficiency of energy [19]

In all aspects, including manufacturing, home living, commercial services and transportation, the government will quickly expand the application of mature technologies to improve energy efficiency. Through economic incentives, educational guidance and mandatory regulations, the aim is to raise the market penetration rate of high-efficiency equipment.

The specific measures are encouraging the manufacturing industry to replace old industrial equipment and use alternative energy sources, such as natural gas, biomass energy and solar energy, guiding users in commercial department with high demand of power to implement the requirements of annually saving 1% electricity energy on average and regulating the energy efficiency of equipment, as well as replacing old equipment such as air conditioning equipment and lighting equipment through means of on-site counseling, promotion activities, tax exemptions or subsidies, etc. For a further step, the government has scheduled to amended the Energy Administration Act to increase the numbers of penalties and to publish lists of violators, etc. In the meantime, the government will develop innovative new energy efficiency technologies and gradually introduce forward-looking technologies to comprehensively improve energy efficiency from the demand side.

Regarding the aspect of transportation, the main strategy is to replace traditional fuel vehicles with electric vehicles. To achieve such goal, the government plans to have urban buses fully rely on electric power by 2030, to have the annual market share of electric cars reach 30% of all new cars by 2030 and to have the annual market share of electric motorcycles reach 35% of all the new motorcycles by 2030. In order to proceed with such transformation, the government is developing upstream and downstream industries related to electric vehicles, and integrating the technical research and development and the establishment of infrastructure such as energy storage, charging piles and safe charging in buildings. As for large tour buses and large trucks for long-distance travel, there will be plans for the electrification for vehicles according to the development of related industry technology.

(e) Strengthening energy storage [20]

The government is proceeding with decentralizing power grids and enhancing their resilience. With the help of IoT technology which enhances system integration and expands energy storage system settings, the aim is to promote the digitization of power grids and improve operational flexibility and adaptability. They will also develop key energy storage technologies, and launch incentives for business models on energy storage.

6. Brief interpretation on the relationship of the Green Trademarks and the policies of Green Industries

(1) The increase of “Green Trademarks” in certain fields may be related to the direction lead by the policies of “Green Industry.”

For several years, the government has been appealing to the public the importance of “Energy Conservation and Carbon Reduction” and has been preparing relevant plans and regulations for building an all-directional “Green Industry.” Following the publishing of the plan for Taiwan’s Pathway to Net-Zero Emissions in 2050, we can see that the government intends to place emphasis on utilizing photovoltaic power, maximizing saved energy and removing carbon emissions.

As “solar Energy” can be applied to various uses in manufacturing, building, transporting or general living and the locations where the installations can be built have less restriction, it is easy to understand that “solar energy” will be the main force of renewable energy. While using renewable energy, it is important to stabilize the provision of energy so that the public will not suffer from black-outs, requires a good system for storing energy. As renewable energy cannot be completely applied to all the use of electricity in Taiwan, there are various non-renewable resource still in use, which would rely on relevant measures to purify the air. Viewing from this perspective, the government’s emphasis placed on strengthening energy storage and removing carbon emissions seems reasonable.

The analysis of Green Trademarks indicates that “solar energy,” “energy saving,” “air purification” and “storage of electricity” are the top categories for applications, each respectively having 27,728, 34,779, 24,867 and 22,504 applications in the ten-year period. This phenomenon seems to reflect that policies implemented in Taiwan under the Net-Zero plan which focus on certain fields have led to an obvious increase in the numbers of Green Trademarks in such fields.

(2) The differences of the development of technology in each field of “Green Industry” may result in the unbalanced growth of “Green Trademarks” in different categories.

Despite that the energy conversion efficiency of hydrogen energy is above 50%[21], which is obviously much higher than the 20% [22] for the conversion efficiency of photovoltaic power, the number of applications for “other energy” in the ten-year period is 12,065, which is far less than the 27,728 for “solar Energy.”

Considering that hydrogen energy technology in Taiwan is currently in the stage of research and development and demonstration, the products that utilize hydrogen energy may be very few in contrast to the ones that use solar energy, which may explain the gap in the numbers of the trademark applications between for “solar energy” and “hydrogen energy.”

The same situation may also explain the low numbers of applications in the categories of “electric car” and “storage of electricity.” However, as some breakthroughs have recently been made in these fields, such as the development of “magnesium-based hydrogen storage materials”[23] and “all-inorganic electrolyte batteries,”[24] a growth of the numbers of applications in these fields is expected.

(3) The numbers of “Green Trademarks” filed by foreign applicants may be subject to consideration of cost.

For most of the categories of Green Trademarks, the number of applications filed by Taiwanese applicants are much more than the ones filed by foreign applicants, but some of the categories of green trademarks are not the same. For example, the numbers of applications in “low energy lighting” filed by foreign applicants in the ten-year period is 109, while the amount filed by Taiwanese applicants is 8.

This is a strange situation, as many places have been using low energy lights, such as street lights, markets, factories and offices. Despite that there are various types of low energy lights available, the common ones are LED and compact fluorescent lamps (CFL).

According to relevant reports, manufacturers in Taiwan were dedicated to the development of LED lighting in early years, for which most of them set their main production base in Taiwan. However, they are now unable to compete with China, which has adopted a low-price strategy, resulting in only a few local manufacturers keeping their business in Taiwan. Since most of the progress of the production of LED lights has moved to China, the domestic need for LED lights is mainly supported by imports.[25]

With this background, we may infer that because the manufacture of LED lights is mainly based in China, other countries were not able to keep pace due to the consideration of cost and thus withdrew themselves from the LED market in Taiwan. The same situation may also explain the low numbers of applications filed by Taiwanese applicants in the categories of “electric engines” and “wind energy.”

Under such circumstance, unless more cost-effective products are further developed, it seems hard to attract applicants in different countries to apply for trademarks in Taiwan, which may serve as a reference for the government on making policy in the future.

(4) The policies are moving toward making the regulations tighter to ensure that the environmental regulations will be complied with.

As we can see in the foregoing introduction of the policies, tax exemptions or subsidies are used as common policy instruments for promoting the relevant programs related to environmental issues. However, the outcomes of such approach may not be ideal.

Taking the goal of promoting energy-saving for example, the vast majority of Taiwan’s commercial service industry is small and medium-sized enterprises, which have relatively limited resources to use. In the cases that the investment in energy-saving equipment is high and electricity accounts for a low part in the costs (accounting for only 1% to 8% of the costs for operation), the business may have limited willingness or ability to replace their old equipment.[26] The government may already be aware of such situation and plan to amend the “Energy Administration Act” by increasing the numbers of penalties and disclosing the violators so that obligations of complying with energy-saving regulations may be imposed to businesses.

Viewing from the foregoing trend, compulsory measures are gradually replacing encouraging measures in the environmental issues, which may imply that the numbers of Green Trademarks of some categories currently with few applications, such as “reusable bottles,” “refilling cartridge,” “biodegradable” and “carbon monitor” may have a chance to increase when the compulsory measures are in effect.

(5) There may be bias with regard to the truthfulness of the numbers of “Green Trademarks” due to the statistical methods applied.

The TIPO defines “Green Trademarks” by the designated goods and services contained in the trademark applications and their Nice classification. According to the TIPO’s report, as long as an application designates at least one green product or service, it will be regarded as a “green trademark,” regardless of whether such mark contains other non-green products or services. Therefore, assuming a case in which a trademark is filed with one application designating twenty green products and a case in which a trademark is filed with ten applications each designating one green product, the former is regarded as only one green trademark while the latter is regarded as ten green trademarks, even if the green products of the former are twice the amount of the latter. Under such circumstances, it seems that each green trademark does not have the equal value.

Since the TIPO collected the data of applications, instead of registrations, the active “Green Trademarks” may be much less than the amount indicated in the report. As there may be questions regarding the description of goods/services or the registrability such as being non-distinctive or being similar to other prior marks, a trademark application may finally be dismissed or rejected by the TIPO. As a consequence, a certain growth rate in the applications for “Green Trademarks” does not mean that such growth rate can also be expected for active “Green Trademarks.”

The TIPO’s report collects applications which designate goods and services that fall in the nine groups and the thirty-five categories of “Green Trademarks.” However, as many applicants would like the scope of protection of their marks to be as broad as possible, they would chose a broader term for the designated goods/services even if they actually produce products that are good for the environment. In that scenario, those marks will not fall in the nine groups and the thirty-five categories and thus will not be considered as “Green Trademarks.” For example, a company produces plastic bags made of biodegradable material. Under the concern that other companies which make plastic bags may use a mark similar to their mark, said company may decide to apply for a trademark designating the goods “bags of plastics, for packaging,” and their mark accordingly will not be deemed as a “Green Trademark.” Assuming that there are a large number of applications having an experience the same or similar to the foregoing example, the actual “Green Trademarks” indicated in the report may actually be underestimated.

Despite the bias with regard to the truthfulness of the numbers of “Green Trademarks” as indicated above, the TIPO’s report still points out the overall trend in each category of “Green Trademarks,” which may provide insights for businesses on how to strategically position their green trademark as well as for the government on how to plan the policies addressing environmental issues.

7. Conclusion

Although the development of technology and the consideration of cost as well as other factors may have an impact on the numbers of “Green Trademarks,” as mentioned above, there is no denying that the policies implemented still serve as the main driving force for the increase of “Green Trademarks.”

Considering that the Net-Zero Emissions have set up goals for various departments related to the “Green Industry,” such as to install offshore wind power of the capacity of 13.1GW before 2030, to install solar photovoltaic installations of the capacity of 30GW before 2030, to have the annual market share of electric cars reach 30% of all the new cars by 2030 and to have the same of electric motorcycles reach 35% by 2030, as well as that the government has plans to tighten up regulations related to environmental issues, it is highly possible that the numbers of “Green Trademarks” for most categories will continue to grow in the following years.

With the expectation of the growth of “Green Trademarks” in the future, it is inevitable that some of “Green Trademarks” will come into conflict with each other, for which a layout for trademarks is advised to be conducted in advance as the same would help the businesses in “Green Industry” in protecting their brand value and reducing the risk of infringement. We at Tai E will of course be pleased to provide any possible assistance with all kinds of trademarks, including “Green Trademarks.”

【References】

[1] Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p. 1-2 (2024)

[2] The website of IGI Global Scientific Publishing, https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/implementation-of-green-considerations-in-public-procurement/70836 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[3] The website of United Nations Industrial Development Organization, https://www.unido.org/our-focus-cross-cutting-services-green-industry/green-industry-initiative (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[4] Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.12 (2024)

[5] Source: European Union Intellectual Property Office, Green EU trade marks Analysis of goods and services specifications, 1996-2020, p.24 (2021)

[6] Source: Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.14 (2024)

[7] Source: Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.16 (2024))

[8] Source: Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.35 (2024)

[9] Source: Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.33 (2024)

[10] Source: Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, The Analysis of Taiwan's Green Trademark Industry (我國綠商標產業布局分析), p.31 (2024)

[11] The website of Executive Yuan, https://www.ey.gov.tw/state/4AC21DC94B8E19A8/bea31948-b13c-4bd7-b13b-904a50ee5730 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[12] Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research, Report of Taiwan’s Green Industry – An overview of Taiwan's Environmental Protection Industry Development (臺灣綠色產業報告-台灣環保產業發展概況), p.6 (2018)

[13] The website of Executive Yuan, https://www.ey.gov.tw/Page/5A8A0CB5B41DA11E/18ef26a4-5d05-4fb3-963e-6b228e713576 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[14] The website of Executive Yuan, https://www.ey.gov.tw/Page/5A8A0CB5B41DA11E/e8819567-8f04-42e1-84ef-cbbe48b5cce2 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[15] Department of Water Quality protection, The 11th Legislative Yuan 3rd session written report material (立法院 11-3 會期書面報告資料), p.1-4 (2024),

https://water.moenv.gov.tw/Public/Download/Policy_law/%E7%AB%8B%E6%B3%95%E9%99%A211-3%E6%9C%9F%E6%9B%B8%E9%9D%A2%E5%A0%B1%E5%91%8A-%E6%B0%B4%E8%B3%AA%E4%BF%9D%E8%AD%B7%E5%8F%B8.pdf

[16] Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research, Report of Taiwan’s Green Industry – An overview of Taiwan's Environmental Protection Industry Development (臺灣綠色產業報告-台灣環保產業發展概況), p.11-12 (2018)

[17] National Development Council, Taiwan's 2050 Net Zero Emissions Pathway and Strategy Overview (臺灣2050淨零排放路徑及策略總說明), p.72-73 (2022)

[18] National Development Council, Taiwan's 2050 Net Zero Emissions Pathway and Strategy Overview (臺灣2050淨零排放路徑及策略總說明), p.74-75 (2022)

[19] National Development Council, Taiwan's 2050 Net Zero Emissions Pathway and Strategy Overview (臺灣2050淨零排放路徑及策略總說明), P.19-31 (2022)

[20] National Development Council, Taiwan's 2050 Net Zero Emissions Pathway and Strategy Overview (臺灣2050淨零排放路徑及策略總說明), P.71 (2022)

[21] The website of Industrial Technology Research Institute, https://www.itri.org.tw/ListStyle.aspx?DisplayStyle=18_content&SiteID=1&MmmID=1036452026061075714&MGID=1307347607677744430 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[22] The website of Green Energy & Environment Research Laboratories, https://www.re.org.tw/news/more.aspx?cid=200&id=2448 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[23] National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, https://www.ntust.edu.tw/p/406-1000-128936,r167.php?Lang=zh-tw (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[24] Chen-Yu Zhang (張宸毓), 2025 CES: ProLogium Technology 's 4th generation lithium ceramic battery achieves 4-minute fast charging along with minus 20 degrees Celsius test, and is expected to be mass-produced by the end of 2025,January 8, 2025,The website of U-CAR, https://news.u-car.com.tw/news/article/82418 (Last visited: May 21, 2025)

[25] The International Trade Administration, Report of Taiwan’s Green Industry – From the perspective of the changes in the Global Lighting Industry to see the Market Trends and Challenges (台灣綠色產業報告-由全球照明產業轉變,看市場發展趨勢與挑戰), p.9 (2018)

[26] National Development Council, Taiwan's 2050 Net Zero Emissions Pathway and Strategy Overview (臺灣2050淨零排放路徑及策略總說明), p.80 (2022)