More Details

1. Preface

Since trademarks are crucial for identifying the sources of goods or services, similar trademarks may easily mislead consumers and cause confusion. This article examines the court’s opinion in a case, i.e., Civil Judgment 2023 Min Shang Shang Zi No. 8 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court, involving the sport fitness brand “AROO” as an example to provide a brief discussion on the assessment of likelihood of confusion.

2. The two parties’ claims[1]

iROO International Co., Ltd. (herein referred to as iROO) claimed that they owned several registered iROO trademarks which had become famous through long-term promotion, while WEI I INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. (herein referred to as WEI I) used the similar mark “AROO” in the identical or similar fields of apparel and online retailing including websites, social media, Shopee online shop, products and packages, etc. iROO deemed such use was likely to cause confusion, thereby constituting trademark infringement as stipulated under Subparagraph 3 of Paragraph 1 of Article 68 of the Trademark Act. Further, as iROO trademarks are well-known trademarks, using AROO as a domain name or a prominent part of a social media account name would also constitute trademark infringement under Subparagraph 2 of Article 70 of the Trademark Act.

3. The court’s judgment

(1) Use of trademark

The court held that WEI I has prominently displayed the mark “AROO” on their website, social media platforms, and Shopee online shop, used “AROO” as a prefix in product names, and placed a stylized logo “AROO” on the front of its apparel. These uses should objectively be deemed sufficient for consumers to identify the source of the goods and constitute trademark use. Moreover, WEI I’s separate application for a trademark consisting solely of the stylized logo “AROO” demonstrates a subjective intention to use “AROO” as an indication of source.

In contrast, the domain name “aroo.com.tw,” the Shopee online shop avatar, shop descriptions, and social media account names merely serve to identify the business entity. According to general concepts prevailing in society and market trading practices, such uses should not be considered as indications of the source of goods and therefore do not constitute use as a trademark.

(2) Likelihood of confusion

When comparing the two parties’ marks, both marks contain the same foreign letters “ROO,” and the only discrepancy are the initial letters “A” and “i.” Since the letter “i” is italicized, it resembles the letter “A.” Furthermore, since the two parties’ marks also have similar pronunciation sounds, their degree of similarity is not low. In addition, WEI I’s use of “AROO” on fitness apparel and related goods is identical or highly similar to “sportswear” in Class 25 and “retailing of apparel” in Class 35 designated by the “iROO” trademarks. Although WEI I argued that the sales channels and target consumers were different, both men’s and women’s clothing are for humans and share similar functions and channels, and therefore this argument cannot be accepted. Further, a market survey jointly commissioned by both parties showed that more than fifty percent of respondents believed that the two trademarks came from the same or different but related sources. In addition, the court accepted the evidence of actual confusion presented by iROO, including online comments in which consumers mistook AROO’s products for those of iROO or inquired about the relationship between the two brands.

(3) “iROO” is not a well-known trademark

Although iROO provided evidence showing celebrities endorsements, advertisement sponsorships and media reports, the court held that most of such evidence consisted merely of internal marketing materials, and such materials cannot prove their market share, brand value and the degree of consumer recognition. Moreover, the aforesaid market survey also showed that only about thirty percent of consumers were aware of “iROO,” i.e., there is no widespread consumer recognition. Accordingly, the court ruled that “iROO” has not reached the high threshold of being “well-known” as required by Subparagraph 2 of Article 70 of the Trademark Act.

The court ultimately concluded that the use of “AROO” in the domain name “aroo.com.tw” may be retained, and that there is no need to remove the wording similar to “iROO” from the website, Shopee shop avatar, shop descriptions, or social media account names. However, the court held that “AROO” is similar to “iROO,” and therefore trademark infringement is still established.

4. Conclusion and comments

(1) The comparison of the initial letters of marks when examining likelihood of confusion

According to Point 5.2.6.6 of the Examination Guidelines on Likelihood of Confusion[2], for alphabet-based foreign languages, the appearance and pronunciation of the initial letters have a substantial impact on the overall impression conveyed to consumers; therefore, the beginning of words is generally given greater weight when assessing trademark similarity. However, even if the initial letters are identical, their comparative weight should be reduced when they are less distinctive in relation to the designated goods or services, or when the accompanying wording clearly conveys a different meaning. This Examination Guidelines is reflected in recent judgments by the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court.

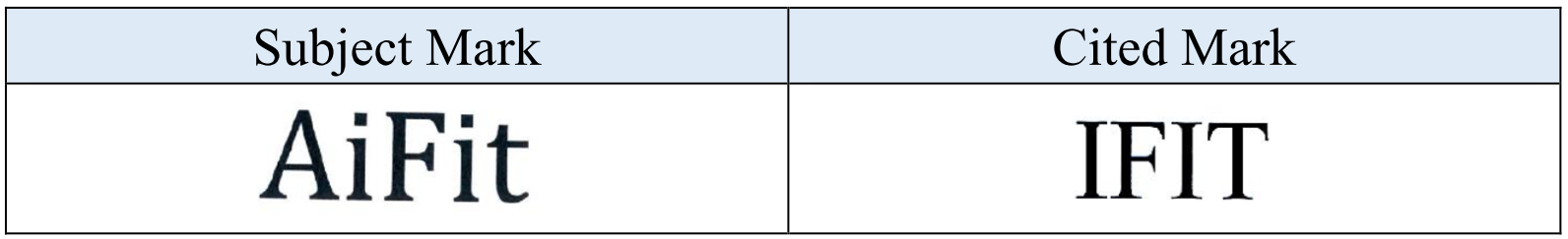

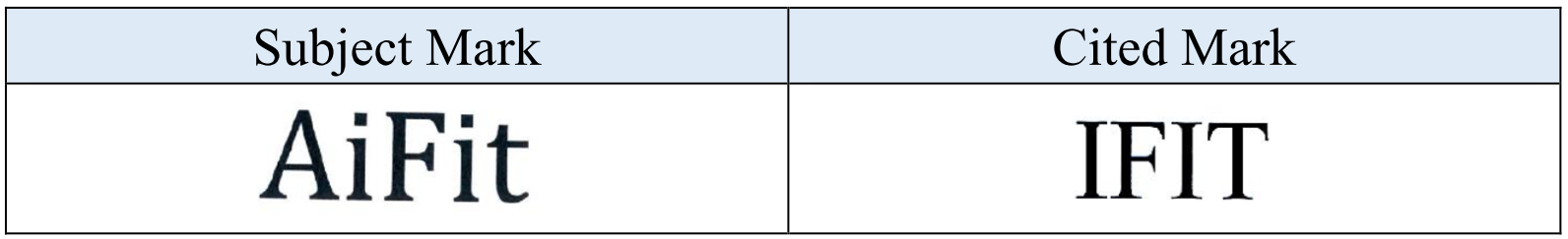

In Administrative Judgment 2023 Xing Shang Su Zi No. 29[3], although the initial letter of the Plaintiff’s mark was “A” and the capitalization of the letters “iFit/IFIT” was different, the marks (as shown in the table below) were considered highly similar in appearance, and both could be pronounced the same, namely [aɪ-fɪt]. As the two marks are similar in appearance and pronunciation, if these marks are labeled on the identical or similar services, consumers may mislead that such services are coming from the same providers, or different providers of related connection.

Accordingly, even if the initial letters are different, there still remains a risk that two trademarks will be considered similar when the remaining letters are identical.

(2) The submission of a credible market survey

In this judgment, the market survey jointly commissioned by the two parties has significantly affected the court’s evaluation of evidence regarding likelihood of confusion. As such market survey included both online and on-site research conducted in Taipei City, New Taipei City, Taichung City, and Kaohsiung City, the geographical range has ensured a representative sample size. We may conclude that if a market survey is only instructed by one party, and samples are limited to a single area, it is very likely that the court will refuse to accept the evidence or deem it to have low probative value. On the other hand, according to our previous experience, if questionnaires are designed to reflect the principles of separate comparison and overall observation, they are more likely to be accepted by the court. In contrast, a side-by-side comparison not only cannot accurately reflect the actual purchasing behavior, but also easily overestimates the likelihood that no confusion will occur.

Therefore, if a trademark applicant intends to submit a market survey to demonstrate that relevant consumers are familiar with its trademark and that no likelihood of confusion would arise during court proceedings, the survey plan, sample size, questionnaire design, and related parameters should be carefully prepared. Our firm would be pleased to assist with reviewing survey proposals or providing guidance to ensure that the survey meets the standards typically required by the court.

(3) The actual use should as closely as possible conform to the registered trademark specimen

Under local practices, actual use of a registered trademark by the proprietor in a form differing in elements which do not affect the identity of the trademark according to general concepts in the society shall constitute use of the registered trademark. The expression “not affect the identity” above means that the main features used to identify a trademark are not substantially changed even though there are minor differences in form between the trademark actually used and the trademark as registered, so the two versions leave the same impression on general consumers and are perceived to be the same. On the contrary, if the actual use of a registered mark is different from the registered trademark specimen (e.g., a registered mark is a combination of the word and a logo but only the word is in use), such use will not only face the risk of being deemed as non-use of the trademark, but also make it difficult to claim that such use constitutes the lawful use of a registered mark in the infringement suit.

According to the online database of the Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, WEI I owns the apparel-related trademarks Reg. No. 01995972 “ ” and 02192942 “

” and 02192942 “  . ” However, the actually used mark “

. ” However, the actually used mark “  ” is notably different from the above two marks, which make it difficult for WEI I to claim that such use constitutes the lawful use their own mark. As a practical recommendation, we suggest that, when filing future trademark applications, the applicant should apply for all possible forms of use in order to obtain comprehensive protection. If budgetary considerations are a concern, filing the plain word mark and the device mark separately is also an acceptable approach, as it allows for greater flexibility in the future use of the trademarks.

” is notably different from the above two marks, which make it difficult for WEI I to claim that such use constitutes the lawful use their own mark. As a practical recommendation, we suggest that, when filing future trademark applications, the applicant should apply for all possible forms of use in order to obtain comprehensive protection. If budgetary considerations are a concern, filing the plain word mark and the device mark separately is also an acceptable approach, as it allows for greater flexibility in the future use of the trademarks.

(4) The distinction between domain name use and trademark use

Unlike the first-instance judgment[5] which considered the use of “AROO” in the domain name as use as a trademark, this judgment (i.e., the second-instance judgment) carefully distinguishes between use as a domain name and as a trademark. Specifically, when consumers browse the website and notice the domain name “aroo.com.tw,” they will consider that this domain is established by a store named “AROO” instead of being a trademark. This distinction is commendable since it not only aligns with the general concepts prevailing in society but is also consistent with the amendments to the Trademark Act made in 2011, i.e., deleting constructive infringement of registered trademarks stipulated under Subparagraph 2 of Article 62 of the old Trademark Act. This change helps avoid excessive protection of registered trademarks and prevents trademark holders from obtaining exclusive right over a domain name. If the second-instance judgment had reached the same conclusion as the previous opinion in the first instance, the protection of trademark rights would have been excessively expanded.

In summary, Civil Judgment 2023 Min Shang Shang Zi No. 8 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court provides practical guidance on key trademark examination issues, including factors affecting the likelihood of confusion, the role of market evidence, conformity of actual use to registered marks, and the distinction between domain name use and trademark use. Its insights are valuable for addressing similar cases in the future.

Reference

[1] Civil Judgment 2023 Min Shang Shang Zi No. 8 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court [智慧財產及商業法院112年度民商上字第8號民事判決]

[2] Intellectual Property Office, MOEA, (2021), Point 5.2.6.6 of the Examination Guidelines on Likelihood of Confusion [經濟部智慧財產局,混淆誤認之虞審查基準,頁8。(2021)]

[3] Administrative Judgment 2023 Xing Shang Su Zi No. 29 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court [智慧財產及商業法院112年度行商訴字第29號行政判決]

[4] Civil Judgment 2022 Min Shang Su Zi No. 30 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court [智慧財產及商業法院111年度民商訴字第30號民事判決]

[5] Civil Judgment 2022 Min Shang Su Zi No. 25 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court [智慧財產及商業法院111年度民商訴字第25號民事判決]

[6] Civil Judgment 2018 Min Shang Su Zi No. 48 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court [智慧財產及商業法院107年度民商訴字第48號民事判決]

Since trademarks are crucial for identifying the sources of goods or services, similar trademarks may easily mislead consumers and cause confusion. This article examines the court’s opinion in a case, i.e., Civil Judgment 2023 Min Shang Shang Zi No. 8 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court, involving the sport fitness brand “AROO” as an example to provide a brief discussion on the assessment of likelihood of confusion.

2. The two parties’ claims[1]

iROO International Co., Ltd. (herein referred to as iROO) claimed that they owned several registered iROO trademarks which had become famous through long-term promotion, while WEI I INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. (herein referred to as WEI I) used the similar mark “AROO” in the identical or similar fields of apparel and online retailing including websites, social media, Shopee online shop, products and packages, etc. iROO deemed such use was likely to cause confusion, thereby constituting trademark infringement as stipulated under Subparagraph 3 of Paragraph 1 of Article 68 of the Trademark Act. Further, as iROO trademarks are well-known trademarks, using AROO as a domain name or a prominent part of a social media account name would also constitute trademark infringement under Subparagraph 2 of Article 70 of the Trademark Act.

In response, WEI I argued that “AROO” was a slogan for the Spartan Race (a series of obstacle races) and differed from “iROO” in its initial letter, font style, and pronunciation sound. WEI I further indicated that their products targeted the male fitness apparel market while iROO engaged in women’s fashion. Since the two parties’ marks differed significantly in target consumers and sales channels, no likelihood of confusion would occur. WEI I also indicated that they have never intended to use the wording “AROO” alone for marketing purposes, and the partial extraction of such wording from their registered trademark was merely incorporated into the product as an artistic design, rather than used as an indicator of the commercial origin of the goods. Further, since iROO did not provide any concrete evidences such as advertising expenses or sales figures to prove that their iROO trademarks are well-known, WEI argued that iROO’s demands that WEI I be prohibited from using “AROO” as a domain name or social media account name were groundless.

3. The court’s judgment

(1) Use of trademark

The court held that WEI I has prominently displayed the mark “AROO” on their website, social media platforms, and Shopee online shop, used “AROO” as a prefix in product names, and placed a stylized logo “AROO” on the front of its apparel. These uses should objectively be deemed sufficient for consumers to identify the source of the goods and constitute trademark use. Moreover, WEI I’s separate application for a trademark consisting solely of the stylized logo “AROO” demonstrates a subjective intention to use “AROO” as an indication of source.

In contrast, the domain name “aroo.com.tw,” the Shopee online shop avatar, shop descriptions, and social media account names merely serve to identify the business entity. According to general concepts prevailing in society and market trading practices, such uses should not be considered as indications of the source of goods and therefore do not constitute use as a trademark.

(2) Likelihood of confusion

When comparing the two parties’ marks, both marks contain the same foreign letters “ROO,” and the only discrepancy are the initial letters “A” and “i.” Since the letter “i” is italicized, it resembles the letter “A.” Furthermore, since the two parties’ marks also have similar pronunciation sounds, their degree of similarity is not low. In addition, WEI I’s use of “AROO” on fitness apparel and related goods is identical or highly similar to “sportswear” in Class 25 and “retailing of apparel” in Class 35 designated by the “iROO” trademarks. Although WEI I argued that the sales channels and target consumers were different, both men’s and women’s clothing are for humans and share similar functions and channels, and therefore this argument cannot be accepted. Further, a market survey jointly commissioned by both parties showed that more than fifty percent of respondents believed that the two trademarks came from the same or different but related sources. In addition, the court accepted the evidence of actual confusion presented by iROO, including online comments in which consumers mistook AROO’s products for those of iROO or inquired about the relationship between the two brands.

(3) “iROO” is not a well-known trademark

Although iROO provided evidence showing celebrities endorsements, advertisement sponsorships and media reports, the court held that most of such evidence consisted merely of internal marketing materials, and such materials cannot prove their market share, brand value and the degree of consumer recognition. Moreover, the aforesaid market survey also showed that only about thirty percent of consumers were aware of “iROO,” i.e., there is no widespread consumer recognition. Accordingly, the court ruled that “iROO” has not reached the high threshold of being “well-known” as required by Subparagraph 2 of Article 70 of the Trademark Act.

The court ultimately concluded that the use of “AROO” in the domain name “aroo.com.tw” may be retained, and that there is no need to remove the wording similar to “iROO” from the website, Shopee shop avatar, shop descriptions, or social media account names. However, the court held that “AROO” is similar to “iROO,” and therefore trademark infringement is still established.

4. Conclusion and comments

(1) The comparison of the initial letters of marks when examining likelihood of confusion

According to Point 5.2.6.6 of the Examination Guidelines on Likelihood of Confusion[2], for alphabet-based foreign languages, the appearance and pronunciation of the initial letters have a substantial impact on the overall impression conveyed to consumers; therefore, the beginning of words is generally given greater weight when assessing trademark similarity. However, even if the initial letters are identical, their comparative weight should be reduced when they are less distinctive in relation to the designated goods or services, or when the accompanying wording clearly conveys a different meaning. This Examination Guidelines is reflected in recent judgments by the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court.

In Administrative Judgment 2023 Xing Shang Su Zi No. 29[3], although the initial letter of the Plaintiff’s mark was “A” and the capitalization of the letters “iFit/IFIT” was different, the marks (as shown in the table below) were considered highly similar in appearance, and both could be pronounced the same, namely [aɪ-fɪt]. As the two marks are similar in appearance and pronunciation, if these marks are labeled on the identical or similar services, consumers may mislead that such services are coming from the same providers, or different providers of related connection.

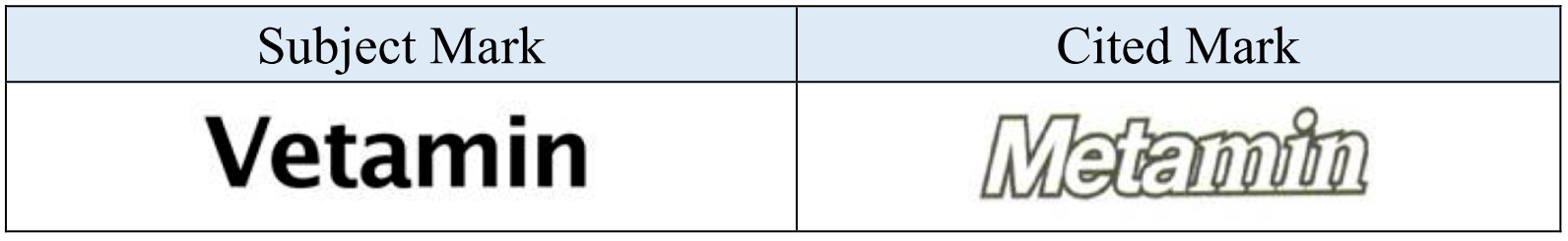

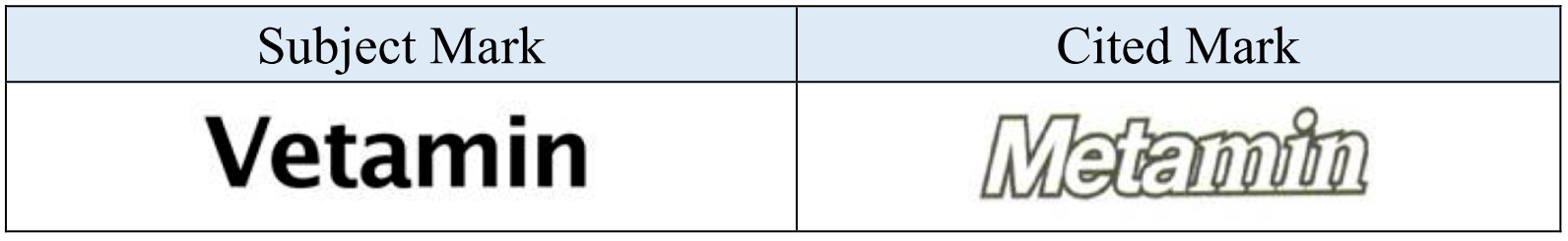

Moreover, in the Civil Judgment 2022 Min Shang Su Zi No. 30[4], the court considered that, for the parties’ marks (as shown in the table below), apart from the difference in the initial letters “M” and “V,” the remaining letters “etamin” were the same, thus causing the overall appearances to be extremely similar. Further, their pronunciations are also highly similar. Therefore, since the two marks contain no distinguishable differences in appearance, font type, and the pronunciation, consumers with common knowledge and experience, when exercising a normal level of attention, may be confused into believing that the goods originate from the same source or from different sources that are related.

Accordingly, even if the initial letters are different, there still remains a risk that two trademarks will be considered similar when the remaining letters are identical.

(2) The submission of a credible market survey

In this judgment, the market survey jointly commissioned by the two parties has significantly affected the court’s evaluation of evidence regarding likelihood of confusion. As such market survey included both online and on-site research conducted in Taipei City, New Taipei City, Taichung City, and Kaohsiung City, the geographical range has ensured a representative sample size. We may conclude that if a market survey is only instructed by one party, and samples are limited to a single area, it is very likely that the court will refuse to accept the evidence or deem it to have low probative value. On the other hand, according to our previous experience, if questionnaires are designed to reflect the principles of separate comparison and overall observation, they are more likely to be accepted by the court. In contrast, a side-by-side comparison not only cannot accurately reflect the actual purchasing behavior, but also easily overestimates the likelihood that no confusion will occur.

Therefore, if a trademark applicant intends to submit a market survey to demonstrate that relevant consumers are familiar with its trademark and that no likelihood of confusion would arise during court proceedings, the survey plan, sample size, questionnaire design, and related parameters should be carefully prepared. Our firm would be pleased to assist with reviewing survey proposals or providing guidance to ensure that the survey meets the standards typically required by the court.

(3) The actual use should as closely as possible conform to the registered trademark specimen

Under local practices, actual use of a registered trademark by the proprietor in a form differing in elements which do not affect the identity of the trademark according to general concepts in the society shall constitute use of the registered trademark. The expression “not affect the identity” above means that the main features used to identify a trademark are not substantially changed even though there are minor differences in form between the trademark actually used and the trademark as registered, so the two versions leave the same impression on general consumers and are perceived to be the same. On the contrary, if the actual use of a registered mark is different from the registered trademark specimen (e.g., a registered mark is a combination of the word and a logo but only the word is in use), such use will not only face the risk of being deemed as non-use of the trademark, but also make it difficult to claim that such use constitutes the lawful use of a registered mark in the infringement suit.

According to the online database of the Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, WEI I owns the apparel-related trademarks Reg. No. 01995972 “

(4) The distinction between domain name use and trademark use

Unlike the first-instance judgment[5] which considered the use of “AROO” in the domain name as use as a trademark, this judgment (i.e., the second-instance judgment) carefully distinguishes between use as a domain name and as a trademark. Specifically, when consumers browse the website and notice the domain name “aroo.com.tw,” they will consider that this domain is established by a store named “AROO” instead of being a trademark. This distinction is commendable since it not only aligns with the general concepts prevailing in society but is also consistent with the amendments to the Trademark Act made in 2011, i.e., deleting constructive infringement of registered trademarks stipulated under Subparagraph 2 of Article 62 of the old Trademark Act. This change helps avoid excessive protection of registered trademarks and prevents trademark holders from obtaining exclusive right over a domain name. If the second-instance judgment had reached the same conclusion as the previous opinion in the first instance, the protection of trademark rights would have been excessively expanded.

We can also find similar opinions in the Civil Judgment 2018 Ming Shang Su Zi No. 48 made by the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court[6]. In this judgment, the judge indicated that the registration of a Facebook fan page account cannot be considered as the use of a trademark. The action of trademark infringement stipulated under Subparagraph 2 of Article 70 of the Trademark Act cannot be directly applicable to the registration of a Facebook fan page account. Whether a trademark infringement is constituted should be primarily based on the overall use of the account name and the content in the fan page.

In summary, Civil Judgment 2023 Min Shang Shang Zi No. 8 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court provides practical guidance on key trademark examination issues, including factors affecting the likelihood of confusion, the role of market evidence, conformity of actual use to registered marks, and the distinction between domain name use and trademark use. Its insights are valuable for addressing similar cases in the future.

Reference

[1] Civil Judgment 2023 Min Shang Shang Zi No. 8 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court [智慧財產及商業法院112年度民商上字第8號民事判決]

[2] Intellectual Property Office, MOEA, (2021), Point 5.2.6.6 of the Examination Guidelines on Likelihood of Confusion [經濟部智慧財產局,混淆誤認之虞審查基準,頁8。(2021)]

[3] Administrative Judgment 2023 Xing Shang Su Zi No. 29 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court [智慧財產及商業法院112年度行商訴字第29號行政判決]

[4] Civil Judgment 2022 Min Shang Su Zi No. 30 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court [智慧財產及商業法院111年度民商訴字第30號民事判決]

[5] Civil Judgment 2022 Min Shang Su Zi No. 25 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court [智慧財產及商業法院111年度民商訴字第25號民事判決]

[6] Civil Judgment 2018 Min Shang Su Zi No. 48 of the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court [智慧財產及商業法院107年度民商訴字第48號民事判決]